The history of textile collections

Textile Recycling is probably the oldest recycling industry in the World

An association of “Rag Collectors” is reputed to have been formed in 50AD by Christian slaves captured by the Romans. The 150th anniversary of this association is fully recorded in the archives of the Roman Empire in Milan. The rag collectors were taken by the Romans in their conquest of Britain and other lands back to Rome and its environs. To clothe themselves and their families the slaves took up rag collection when Christianity finally established itself in Rome, the slaves were released to return to their homeland where they continued the task of collecting rags.

Moving on to the 16th Century, the rag-and-bone trade was officially established in 1588 when Elizabeth I granted privileges to mud larks and to those who collected rags for making paper.

Rag-and-bone men continued to be a common site in British towns and cities for almost the next 400 years. They would collect unwanted household items and sell them to merchants. Traditionally they would walk around on foot and call out to householders to bring out their rag and bone. The collected items were often kept in a small bag slung over their shoulder. Some wealthier rag-and-bone men used a cart, sometimes pulled by horse or pony.

The rag and bone men of the 19th Century were often extremely poor, surviving only on their daily proceeds. Following World War II conditions got better as the standard of living in Britain improved, but the trade declined during the latter half of the 20th century. Lately, however, due in part to the rise in value of both scrap metals and textiles, collectors have once again been seen in the UK, although the 21st Century “Rag and Bone” man no longer has a horse and cart but will often be seen driving around in a van.

Another important turning point in the modern era of textile recycling can perhaps be traced back to Benjamin Law.

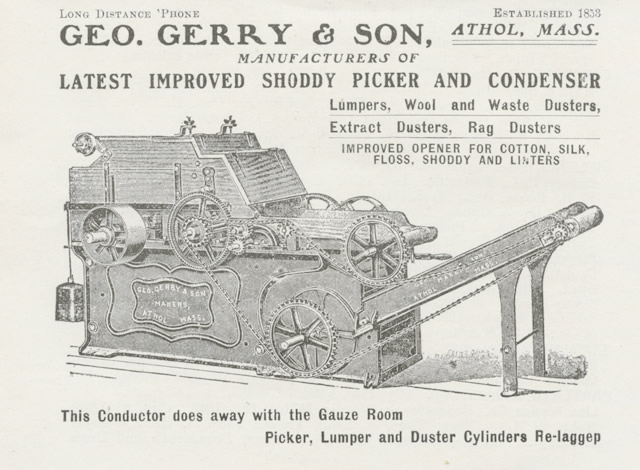

He was born around 1773 in Gomersal, Yorkshire and is credited by many authors as the inventor of the shoddy process. It was around 1813 when he decided to try and mix finely shredded rags with virgin wool to produce the woven cloth “shoddy” which had a profound impact on the textiles industry.

Because of the Napoleonic wars, trade embargos meant that there was insufficient yarn to meet the demands of weavers. Before the industrial revolution spinning was a slow process compared to weaving. Spinning wheels greatly increased the speed but still many more spinners were required than weavers. With the invention of spinning and carding machines, the spinning process was finally able to keep up the weaving process. The cloth industry then grew at a rapid rate. The increased demands for cloth created a need for more raw materials and out of this need shoddy was born.

When Benjamin Law developed the process of making shoddy, he was unable to figure out a way of incorporating tailor’s clippings into the process. This was figured out by his nephews several years later and was called “mungo”. By 1855, 35,000,000 pounds of rag were being sorted and processed into yarn make “mungo” and “shoddy”. Woolen yarn and worsted (a yarn consisting of straight parallel fibers) were used to make “mungo” and “shoddy”. Cotton rag was used to make paper.

The Textile Recycling Association – The Early Years

The Beginning

The actual launch date of the Association is difficult to pinpoint as there are no early records. The Association, originally called the Metal and Waste Traders Association (MWTA), first surfaced in December 1913, when it is recorded that the Association had a registered office in Arundel Street, near the Strand in London, WC2.

However, it is not until 1916 that the earliest of a record of a meeting was found. The names of members who were present at the meeting indicate that the association covered just about every aspect of the materials reclamation industry that existed then. It is also apparent that most of them were engaged in the collection, sorting and processing of rags.

During the war severe restrictions were placed on the industry which limited the movement of goods. Indeed, proposals were put in place to restrict the collection of metal and rags to local authorities only, who would then supply the industry. The thinking behind this proposal being that the local authorities would be able to operate the most efficient collection and supply chain to the industry. Of course, though, the idea of preventing businesses from securing their own supply of used rags and metals was strongly contested and the proposal was defeated. However, the failure of this proposal reportedly soured the relation between the traders and local authorities and relationships remained difficult after the end of World War I.

The war with all its regulations, restrictions and byelaws did much to weld the trade together. It resulted in a proliferation of organizations throughout the country, but none was a strong as the MWTA. For this reason, its advice and support of different causes was always sought by other key stakeholders. Towards the end of the World War I, the MWTA’s offices had moved to 37 Norfolk Street, London WC2.

Whilst we now have the luxury of hindsight, during the difficult years of the first half of the 20th Century, particularly when the UK was at war, it was hard to appreciate what contribution the waste reclamation industry made to the national economy. During World War I it is on record that the following were recovered:

- over 230 million lbs. (105 million kg) of wool.

- 2 million tons of metal scrap.

- 500,000 tons of bones which was used to make 25,000 tons of glycerines for use in explosives.

- 50,000 tons of edible fats.

- 20,000 tons of glue; and

- 25,000 tons of waste rubber.

In addition, some 40 to 50 million rabbit skins were traded to the hat and fur industries for use in military uniforms.

There were around 1,700 factories throughout the country manufacturing wool and wool products, almost all dependent on recovered wool. Wastepaper during the World War I was a comparative newcomer with up to 650,000 tons being recycled annually.

In 1934 the “Waste Trade Federation” was amalgamated into the MWTA, which temporarily swelled membership numbers to over 800 firms. However, the great slump was still exerting its devastating effect on industry in the UK and abroad and it had such a dramatic effect on the membership levels that by 1937 it was feared that the association would have to close.

Fortunately (at least as far as the UK was concerned) the economy started improving in the few years leading up to World War II and when the war broke out Britain suddenly had to make do and mend even more with its limited resources. This propelled the importance of the reclamation industry further up the agenda. Collectively the members of the MWTA were able to face all the issues that ensued in World War II, notably National Service, wage fixing, schedule of reserved occupations, petrol supplies, clothes and food rationing and the problems caused by the Prevention of Crimes Act 1871. The trade generally battled against the provisions of this Act for over 40 years, and it is credit of this association that it ultimately achieved what other associations had failed to do.

The Association had to deal with all such matters on their members’ behalf and it was very difficult to convince the Directorate of Home-Produced Raw Materials that there had to be more flexibility, if the trade were to do the job, they were experts at.

Another effect of the war was that manufacturing increased substantially but because most goods produced were for use by the armed forces in combat abroad, the availability of material for recovery became scarcer. The Reclamation Association (as it was then known) had to call on the Government to co-ordinate the recovery of all re-useable raw materials and encourage the British public to do the patriotic thing and recycling everything.

As the war continued, transport became an increasing problem. Petrol and other fuels were rationed, and the country was divided into regions with licenses required to move raw materials from one part of the country to another. The Government were so concerned about shortages that they imposed compulsory obligations on local authorities to increase the salvage of a variety of waste materials including textiles, wastepaper, and food scraps for animal feed. The industry was threatened by many problems which kept senior association representatives constantly in negotiation with Government departments on such subjects as freight and rail rates, wage rates, insurance, price margins etc.

The Ministry of War Transport was also constantly pressing for petrol to be used more efficiently. They “asked” for voluntary agreements to be invoked whilst at the same time threatening industry with compulsory legislation if satisfactory agreements could not be reached. A common agreement to restrict the transportation of goods in most circumstances to a limit of 25 miles radius from each businesses warehouse was reached. However, although it sometimes proved necessary, circumstances arose where the railways could not or would not accept goods for further distance travel. It took the association many months to get the Ministry of War Transport to agree that in these circumstances supplementary petrol could be applied for. Generally, throughout the war the situation of the reclamation industry became more and more complex and association members had to operate under an increasing plethora of control orders. When the war ended in 1945 it was thought that normality would return quickly, but this was not so.

This done, the then General Secretaries of both organizations, Mr. A P Hughes (WTF) and Mr. G Walter Lloyd (BSF) travelled to Amsterdam and Brussels to negotiate the formation of an international federation which would bring together all similar organizations in Europe. The negotiations were successful and in 1948 the Bureau of International Recycling was formed and held its first meeting. The success of that organization is well documented and many leading members of the Textile Recycling Association (and before that the Reclamation Association) have worked hard and long to ensure its continuing success.

The Modern Era

Charity Shop Collections

The advent of the charity shop is a relatively modem phenomenon. The Red Cross opened their first shops in 1941. These were more like gift shops and the proceeds went to the Duke of Gloucester’s Red Cross and St John Fund.

The first charity shop operated by Oxfam opened in London in 1948. However, it was really in the 1980s that the charity shop sector began to take off. There are now approximately 9000 charity shops in the UK.

Clothing is the most popular type of item that is donated by the public to charity shops and the sale of such items can raise significant funds for the charity. Whether clothing is collected via a charity shop, clothing, and textile collection bank or directly from your doorstep and whether the collection is undertaken with some profits going to charity or on behalf of a local authority or other organization, what happens to clothing is almost the same.

Clothing donated to a charity shop will be sorted by charity shop staff or volunteers. Between 20% and 50% of the total amount donated will be sold in the shop. The remaining items will be sold on by the charity shop to a textile reclamation merchant and the items will go through a further sorting process before being sent for re-use and recycling.

The charity shop can generate income through the sale of garments in their store and through the sale of clothing to the textile reclamation merchants. After the cost associated with the running of the shop has been deducted, the net profit generated is then passed onto the benefitting charity.

Once the items that are not sold in a charity shop are sold on to a textile reclamation merchant the route that the items take are the same as if they were collected through clothing collection banks or door to door collections.

Clothing Bank and Door to Door Collections

Some clothing is collected through clothing collection banks which are often situated in public car parks alongside other recycling banks for materials such as paper, glass, cans, and plastics. Most clothing collection banks are operated by private businesses. In some instances, clothing is collected by legitimate clothing collectors directly from the households. Often collections from banks and households are operated in partnership with charities or local authorities who receive a substantial proportion of the net profits generated from the sale of the clothing collected after costs have been deducted. In some cases, the banks and door to door collections are operated by charity shops which use the banks to stock clothing for their shops.

Once the clothing has been collected by the textile reclamation merchant, the items will then be put through a sorting process. This can either happen in the UK or abroad. The clothing can be put into any one of about 140 grades. It could be graded into re-useable or recyclable grades, its suitability for the main markets of Eastern Europe or Sub Saharan Africa, by garment and many other factors.

From Fiber Reclamation to Used Clothing and Back?

However, the move by the industry from that of being one that was mainly driven by the need to recover and recycle fibers to one dominated by the collection, sorting and export of clothing for re-use is relatively recent.

In the Reclamation Association’s report to its members for its 75th Anniversary in 1988, there is hardly any mention of charity shops at all. It merely makes reference to them as being a source for the recovery of “textile waste” and the report makes reference to the uses of recovered textiles being “many and various – knitted or woven woolen rags, when processed, result in mungo or shoddy fibers used extensively in the woolen industry to make heavy cloth for uniforms, coats, blanks, carpets, furs etc., whilst cotton and linen (flax) rags are used by the paper mills for making quality papers for use in ledgers, banknotes and stationery. Jute cloths are recovered in the form of sacks and bags which are repaired, cleaned and fumigated and returned for re-use to farmers, chemical manufacturers, corn merchants etc.” and the list goes on.

The current model for “textile recovery” is somewhat different.

The proliferation of the charity shops and clothing collection banks were possible in part because of the opening of the African export markets in 1980s and the Eastern European market in the 1990s.

However, membership during this period declined from over 50 members in the early 1990s to a little over 30 members by the end of the decade. This was due in part because as recycling of domestic waste started to become more “normal” amongst a small section of the committed public in the 1980s (a habit that was largely lost in post war prosperous 1960s Britain). Collectors and processors of other waste materials started requiring more sector specific help and whilst retaining a close relationship with the Reclamation Association, they started forming their own trade bodies and peeled away from the Reclamation Association. Although in 1993 the Wiping Cloth Manufacturer’s association merged into the Reclamation Association.

In 1992, the membership decided that to promote working partnerships with local authorities and charities that would increase clothing and textile collections a new UK wide bonded textile recycling scheme should be launched and “Recyclatex” was born. It had notable successes in securing some national collection contracts with charities and it raised the profile of the association at the time. Some 16 members of the Reclamation Association initially joined the Recyclatex scheme and its relationship with the TRA throughout the 1990s was close. However, whilst “the Recyclatex Group” is still going strong today, it formerly severed its links and became an independent body the early 2000s.

At the Annual General Meeting in 1996, Mr. Keith Barnes put forward a proposal to change the name of The Reclamation Association to the Textile Recycling Association “to reflect more accurately the trade covered by the membership of the day”.

The proposal was ratified at a Special General Meeting held at the Great Northern Hotel in King’s Cross on 22nd April 1996, which followed a consultation of all members, and which showed unanimous support for the proposal.

By the turn of the Millennium, the number of charity shops on the UK high street had started to increase and indeed they had formed their own trade association (what is now the Charity Retail Association) and with the general awareness of the need for recycling, flows of textiles arriving at UK used textile processors were steadily rising and despite some moderate price fluctuations things were OK for a while.

In 2003, the Textile Recycling Association decided to appoint a full-time manager with a remit to promote the interests of its members locally, nationally, and internationally and to lobby directly with the UK Government, EU, and other relevant bodies and to increase the membership numbers. They appointed Alan Wheeler as their new National Liaison Manager. In 2003 the membership of the TRA stood at 32 and the budget for the TRA was so tight that membership fees had to be called in a few weeks early to ensure that the association did not go insolvent in 2004. Since then, the trade association’s own position has improved substantially with 56 members in 2013 and much stronger finances.

The profile of the TRA has also increased significantly and textile recycling has become national news, sometimes for good reasons. The trade association has also enjoyed some significant successes through direct representation to the EU and UK Government. Of note was the success in getting MEPs to agree to include textiles on the list of priority wastes for consideration as to when textiles should cease to be classed as waste and for this definition to be applied across all EU member states. Whilst textiles have been included on this list, the process of defining when textiles should cease to be waste throughout the EU has still to be concluded.

Whilst this matter is on-going in Europe, the UK industry has been successful in persuading the Environment Agency to take a pragmatic view when it comes to the classification of waste as it is applied to used textiles and to consider it largely to be a resource. As a result of this, many textile collectors and sorters enjoy a much less dogmatic and stifling application of EU regulations than their European counterparts, at least while the goods are in the UK.

In addition, after several years of lobbying the textile industry finally got recognition of the contribution it can play in reducing the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, when in 2007, the Government published its Waste Strategy for England and recognized that the carbon impact of diverting textiles away from landfill was significantly higher than all other household waste streams on a per ton basis except aluminum.

Consequently, the UK Government eventually conceded that it needed to start looking at the impact of textiles and in 2008 DEFRA launched the inaugural conference of the Sustainable Clothing Roadmap. In 2011 this was taken over by Waste Resources Action Programme (WRAP) and renamed the Sustainable Clothing Action Plan (SCAP).

When SCAP came to a conclusion in 2020 the TRA continued to support WRAP and became a founding supporter of the brand new industry led voluntary scheme Textiles 2030. This has set targets and ambitions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption and circularity targets by 2030. The TRA also sits on the steering committee of Textiles 2030 as well as a number of its key policy working groups.

Despite difficult trading conditions the reputation of the TRA continues to go from strength to strength, with the associations CEO Alan Wheeler, now sitting on the Government’s Advisory Group to DEFRA’s Resources and Waste Strategy. He is the only textiles industry specialist on this group. Whilst on the international stage the TRA continues to forge important partnerships and impacts through our high level representation at the Bureau of International Recycling, the European Recycling Industries Confederation and other international partnerships.

In 2023 the TRA was delighted to be part of successful bid for a £4 million grant funded by Innovate UK to deliver an Automated Textile Sorting Plant and we look forward to working with our partners in 2025 and beyond to make this a reality and transform the textile recycling industry in the UK and globally.

We will also continue to work with UK Government to deliver its priorities for textiles which it set out in its 2023 strategy Maximising Resources, Minimising Waste whilst working with Government departments and politicians to take the necessary bolder steps that can actually deliver a sustainable clothing and textiles industry with re-use and recycling playing a pivotal role.